Writer's Journal

On Reading

Lately my reading “stack” has been growing unruly with threads leading me to somewhere dimensionally obscure, tugging on time-worn snags in the pneumatic armature of the universe, wrapping me up in one of those webs of dim intuition that people like me fashion for themselves reflexively, for no reason other than instinct and habit.

Sometimes I think it’s my actual vocation to read books — not to write about them, to comment on them, to write them myself, or to become an expert in some classificatory register or wing of the topoi, but to just sit and read them, in the morning as the light of truth daubs the clearings and prairies of the world, in the evening as the flames of night hatch from caves into the dreams of passers-by, and in the seconds of the day that pile up on one another, begging for the next and slipping out of view in a slumped and crosshatched rhythm.

Reading more than anything is a way of organizing my life according to a time that rings the spheres with meaning. My mother was a librarian; indeed, a children’s librarian when I was a child, so in many ways I feel I’ve emerged out of books and into the world. Sometimes when I’m reading I feel like I know what the vibe might have been like in Babel before the tower fell and we were scattered across the earth to wander between tongues. I know this is an illusion, but it keeps me turning the page.

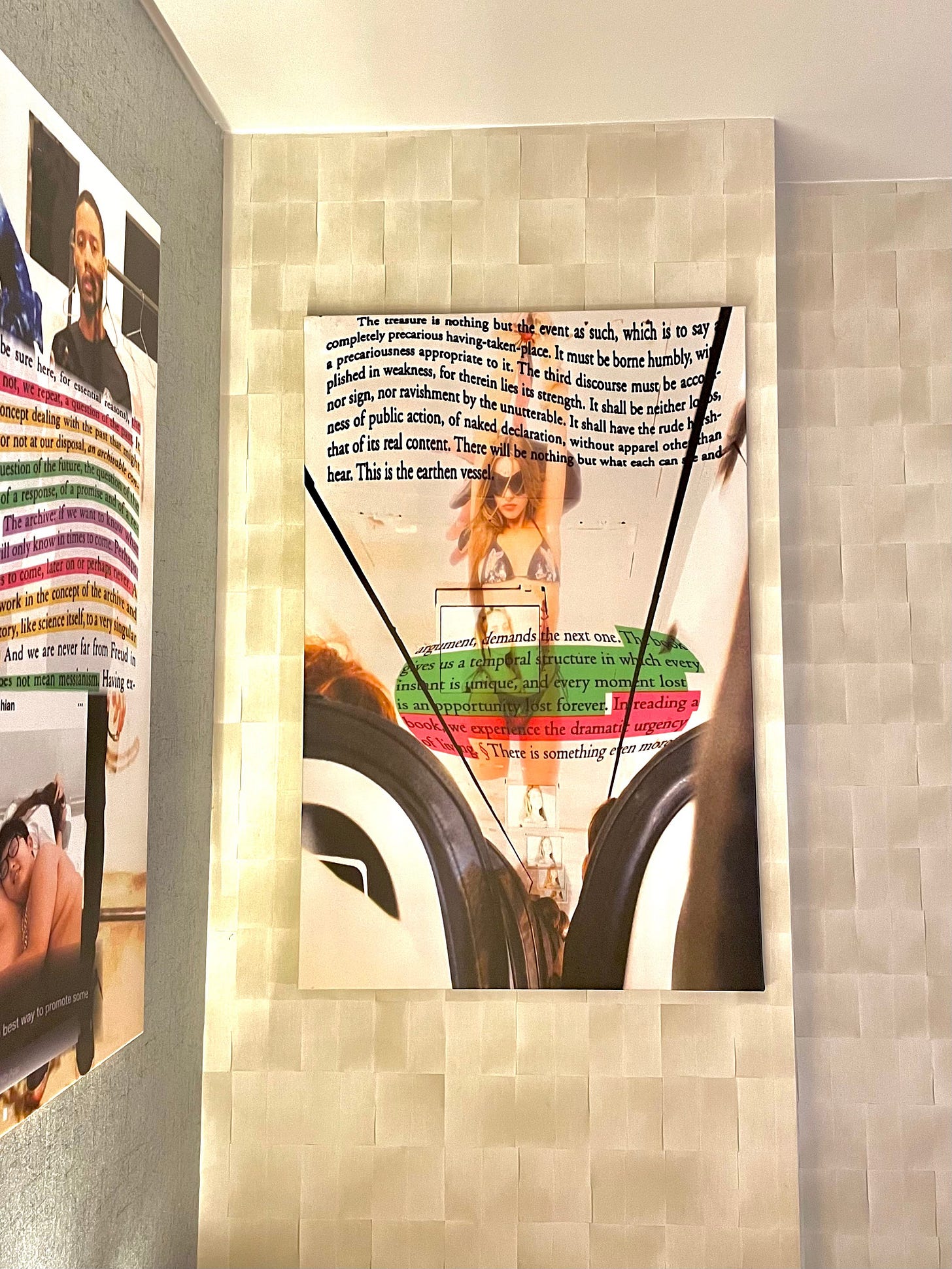

I have a piece of art hanging in my living room that was made by the Twitter personality and writer

. It prominently features a quote from the heterodox Czech media theorist and philosopher Vilém Flusser, set in front of a foreground shot of the model Alana Champion, over a background of what looks like the POV view of sitting in the seat of an airplane gazing towards the front. The Flusser quote derives from a short and relatively straightforward article he wrote for Artforum in the diabolical year of 1991, simply called “Books.”Two of Flusser’s books — The History of the Devil and Vampyroteuthis Infernalis — were quite influential to me, but I didn’t realize that the quote was from him until I got the print in the mail and Googled the text.

[The other quote on the print is from Alain Badiou’s Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism, a book that I ended up buying and reading and which ultimately contributed to my conversion. That’s another story, however.]

In the “Books” essay, Flusser comes to the defense of books and their “addicts,” not at all for what books specifically contain, but for what they fundamentally do as media objects. In a strictly material sense they are basically worthless, heavy, inefficient as transmitters of information, and a burden to us “measurable in kilos, cubic feet, and hours.” Why do we submit to them “as an addiction”?

The act of reading books is fundamental to the reciprocal grace of worldly expatriation and cosmic repatriation so obsessively sought by those Flusser calls “us addicts” — there is an ethic and a rhythm of life pressed into the strings of letters that keep calling to us, against our worldly knowledge:

The detour through language on the way from thought to book is what they love most: the information itself may even count less than the particular way in which it has been pressed into word, sequence, sonority. When we open a book we participate in a conversation that has carried and elaborated information almost since the beginning of our species. More—we become responsible for its continuation. When we look at an image our eyes scan the surface in circles, and the circle enforces eternal repetition. In a book, on the other hand, our eyes follow the lines of the text, progressively collecting the information, and thus the line carries us toward the future. Each sentence, each argument, demands the next one. The book gives us a temporal structure in which every instant is unique, and every moment lost is an opportunity lost forever. In reading a book, we experience the dramatic urgency of living.

Before I went on retreat a few weeks ago I went to Magers & Quinn Booksellers in uptown Minneapolis and bought three books, spending about $40. I hadn’t bought any books from a bookstore in awhile. There’s something special about buying books in this way, intuitively, that doesn't hinge on the someone mentioning something to you online or in a podcast, doesn’t stem from research, but from you just seeing something and then thinking oh hell yeah, i’m going to read this.

I bought Joan Didion’s The White Album, which is a collection of essays published together in the early 80s that mainly stands as a reflection on the tumult and psycho-spiritual mayhem of the late 60s and early 70s in America. I bought an old used copy of Ernest Hemingway’s The Nick Adams Stories, which I’ve always wanted to read because one of them is about trout fishing on the Two Hearted River in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, a place to which I have a family connection. Finally, I bought Jean Genet’s Prisoner of Love, Genet’s final work before his death, a memoir and reflection on his time spent amongst Palestinian refugees and fedayeen in 1970 and 1971. This was a week before the new war erupted in Gaza.

I’m also reading a book that Hank bought me, An Exorcist Tells His Story, by Fr Gabriele Amorth, the man upon whom Russell Crowe’s character in the 2023 film The Pope’s Exorcist is based. I’m also reading a biography and investigation into of the murder of Ioan Culianu, the Romanian scholar of renaissance magic and comparative religions who studied under the controversial religious studies scion Mircea Eliade and was murdered, probably by the Romanian secret police, in a third floor bathroom of the U-Chicago Divinity School in 1991. I still haven’t finished Matteo Pasquinelli’s Marxian social history of “artificial intelligence,” The Eye of the Master, which I told you all (and a publicist at Verso) that I would review. Finally, every morning a read a few pages of The Pocket Thomas Merton, a perennial inspiration, as an aid to prayer and meditation.

I list this out not to show you how much I’m reading, because in truth the way I read is often strained and schizoid, positively unstudious. It’s to affirm that there is some kind of wild temporality in reading that actually interacts with the raw matter of life, and that this desire spreads out in every direction like the arterial cosmos of the interstate system on the plains, gushing towards a drooping horizon in the west. I imagine that when I am old and I see all the books that I’ve read over the course of my life, it will strike me how few they actually are — the temporality of reflection and compilation will never penetrate that dramatic urgency of living which is a living force in those of us addicted to letters on a page that flips.