On Teaching

And how it is and is not like writing

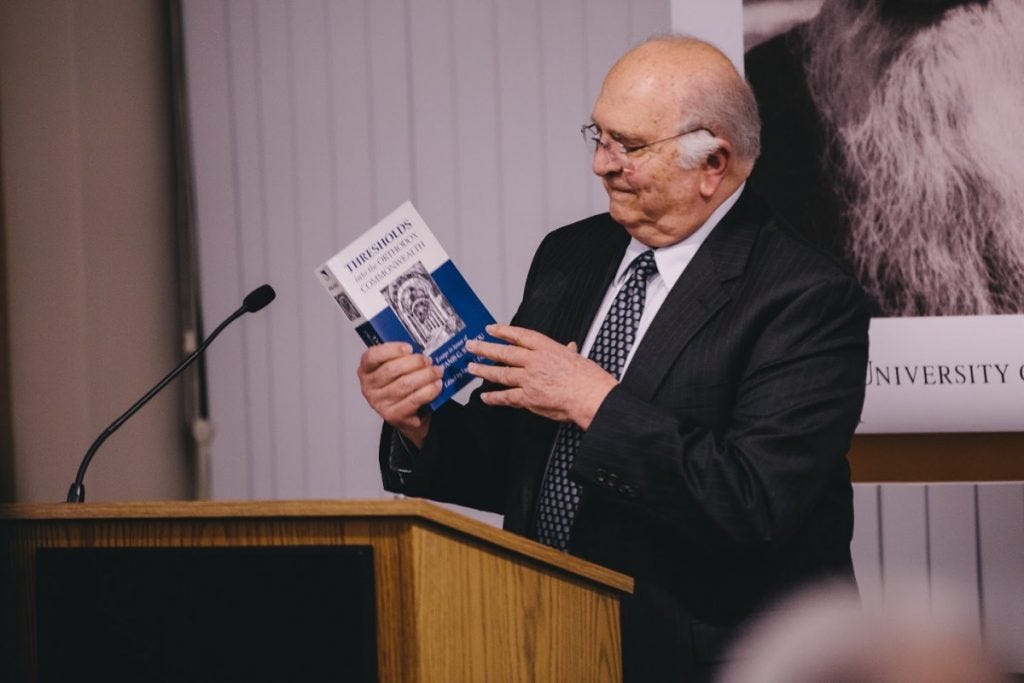

This is the first time I’ve written publicly since I became a full-time teacher in late fall of last year. There are configurations of activity in which teaching and writing can feed one another. When I used to teach undergraduates, I was in the classroom twice a week for roughly 75 minutes. I would wake up at 7am and go to the second wave coffee shop by my house in Northeast Minneapolis, and write my lecture for the day on a piece of paper. Sometimes lined, sometimes not. I did not use a computer, ever, unless I’d failed to print a PDF or something. In doing so I imitated a man named Theofanis Stavrou, who is both an esteemed scholar of Greek and Russian history (he created the Greek Studies department at University of Minnesota), Eastern Orthodox theology, and international relations, and a very cool and sweet 90 year-old man, whose teaching style and generally benevolent demeanor have become all but illegal in the academy.

I got to take Stavrou’s course on 20th Century Russian History while I was at the University of Minnesota. He would enter the room a few minutes before or after the start time with a double-breasted suit and a patient, wobbling gait, carrying one or two pieces of paper on which he’d written, in meticulous chicken-scratch, his lecture for the day. He’d explained to us affably his office hours policy. The door to his windowless, book-lined office on the umpteenth floor of the brutalist “social sciences tower” was literally always open, except for the half-hour period before he was to teach a class: this was, he stated plainly, his praying time.

Stavrou is Orthodox Christian, but we gathered from his delivery that what he meant by prayer was not, in this case, the Jesus Prayer or a hymn to the Theotokos, but simply writing the lecture. Each day he would deliver the lecture, largely from memory, taking questions along the way but making no pretension to the discussion-based format that has become obligatory in liberal arts settings. The lecture itself might have been prayer: this or that detail would set his face alight with the blooming wonder of the Spirit, and he would almost never make it through the full length of what he intended to talk about, lured by the Muse to rejoice in digressions on the social power of Faith, or the particular manner in which Lenin would take the hands of Russian grandmothers and simply hold and study them, or on the strange persistence of suspicion towards the “Slavic Mind” among Americans.

After the lecture, he would throw his prepared notes for the day in the trash, and start anew.

All the best teachers I’ve had past the level of high school taught in this manner. All of them are from the Mediterranean. I will name names: the aforementioned Stavrou, Kiarina Kordela, and Cesare Casarino. Two of them, Stavrou and Casarino, hail from Mediterranean islands. The last two, Kordela and Casarino, I am indebted to for teaching me, non-dogmatically, about Marx and the critique of capital.

Their teaching style, the panoramic lecture, was for me a far more active form of learning than discussion-based seminars. To follow, carefully and with laser attention, the arc of someone’s thinking as they weave through the forest of what is in search of the clearing of Freedom, as they loosens knots but leave them tied for us to study, as they call upon us, gently and without idiotic prompting questions, to force them, in positing our misunderstandings as statements, to take an unforeseen turn and to end up somewhere completely new, is inestimably more impactful than sitting down with a text and circle of students and asking, “So what did you guys think?”

To teach and learn in this style is to participate in a kind of profound social writing, not entirely unlike prayer, and whatever the bankruptcy of the university as institution, it is a practice I will defend and do my best to keep alive, even just among friends, without an institution. The version of this practice that is reproduced in movies and cheap cultural images is reliant on institutions, among friends it is not.

I found out very quickly last fall that to bring this style of teaching to bear upon a room of sixth graders is incredibly, amazingly stupid.

I began the year essentially afraid of children. Despite my probably halting and overly formal presence in the classroom the first few weeks, and the fact that I was their third successive teacher of year, my kids were quick to accept me as their teacher. Sixth graders cannot sit and listen to a planned lecture. It is unnatural to their being as creatures. Developmentally, as the pedagogues are wont to say nowadays, their minds are in a state of acute anarchy. Their curiosity is essentially boundless, probably as expansive as it will ever be, but their ability to patiently follow a thread maxes out after 10 minutes or so. They cannot — they simply cannot — quietly listen to one another share, one at a time. They will shout over one another. One can use as much “classroom management” as one likes, there will always be a time in which their energy is simply an ungovernable surplus. The trick becomes to channel it.

One channels it through the structure of relationships. One develops little routines, little jokes with them. The rapport you have with them is the rapport you have. The trick becomes to stay radically present in the situation. They need structure, but they also need controlled anarchy. They need to be able to move around, but also to be given rules about how to move around.

The form of attention one cultivates in attending to a class of sixth graders is just as prayerful as the state one chases in the lecture-seminar, but in an entirely different dimension: the sixth grade class lays bare that teaching is always essentially relational and that no knowledge exists apart from these relationships. In teaching sixth grade, I learned, in a not always easy manner, that the knowledge, mutually constructed, is the relationship, and nothing else. The seminar at a “higher level” can sometimes make pretensions to existing at the level of abstraction, but it remains fundamentally a room full of human beings talking to one another, whether one leads and the rest follow or they jockey for position. In teaching sixth grade, one learns that care is essentially the form of attention to which you give yourself entirely, and that it has, at this point of concentrated humanity, little to do with writing, with the isolated and monadic desire to overcome one’s isolation and exert on the material an inscription, a graphé, that expresses something. In teaching sixth grade one becomes given over to an ungovernable but cherished community of human creatures, and changed for it. One creates, but one does not have control. There is no writing in this state. There is no withdrawal. One himself becomes an inscription and a testament: I left with a yearbook full of messages from my kids, each of which has no origin within me. It is nothing that I could have made on my own.

It is only because I am on summer break that I am able to write today. I will try to write this summer, but I can’t guarantee that I’ll be able to write again when I start to teach high school English this coming fall. I’m at peace with that.